Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion—Part 7:

Shopping in the 18th Century with Mary Philipse Morris

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, and part 8.

|

Before Eliza Jumel there was Mary Philipse Morris, the first mistress of the Morris-Jumel Mansion. Born into a family of slaveholding landowners, she could afford to marry for love and did, choosing British army officer Roger Morris. With her family money behind them, the couple moved in colonial high society. In the account book of Manhattan haberdasher Samuel Deall, the name "Mrs. Col[onel] Morris" appears amid a roll call of New York's landed gentry and administrators: the Schuylers, the Bayards, the Delanceys, the Apthorpes, the Wattses, William Tryon, and the Hon. Mrs. Gage. For twelve years Mary Morris had an account with Deall, from 1764 to 1776. Her purchases offer a peephole into the private life of a colonial gentlewoman and her family.

|

Deall's shop was located at the corner of Broad and Beaver Streets, just a couple of blocks from the Morris's house in town. Primarily Deall sold trimmings such as ribbons and laces, as well as ready-made accessories including gloves and stockings. He stocked toiletries too, including toothbrushes, hair powder, and shaving brushes, and a miscellany of items demanded by well-off households: pins, birdseed, lamp oil, boot blacking, and specialty foodstuffs as well. In spring and summer he did a good business in garden seeds.

Mary Morris stopped in approximately eight times per year, typically buying one item or occasionally two. The picture is of a woman who shopped selectively when her wardrobe or household needed refurbishing, rather than a lavish spender who bought on impulse.

Mary Morris stopped in approximately eight times per year, typically buying one item or occasionally two. The picture is of a woman who shopped selectively when her wardrobe or household needed refurbishing, rather than a lavish spender who bought on impulse.

|

Mary purchased green, white, black, and scarlet ribbons, as well as stockings knitted of black or white worsted wool. One day she went home with a gauze cap; six months later her choice was a chip (i.e., straw) hat. On another occasion she bought a bottle of lavender water.

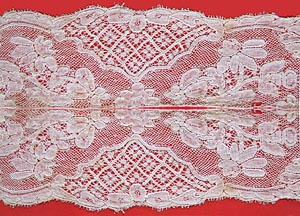

A notation of "double bloon" lace purchased in 1764 may have been a misspelling of "double blonde": strips of lace made from blonde, i.e., undyed, silk (typically off-white or beige), probably designed to be sewn together lengthwise to create a double-width band suitable for trimming a dress. (Given the spelling, we might wonder whether the word "blonde" was pronounced "bloond" in eighteenth-century New York.) |

More rarely Mary made purchases for her husband: a pair of superfine black silk stockings in 1766 and a pair in superfine black worsted wool in 1768. In mid-December of ‘68, she brought home a pair of men's grain lambskin gloves (i.e., leather with a glossy, polished surface) and a pair of women's gloves in French kid (considered a notch up from lambskin in feminine apparel). Perhaps she and Roger were preparing for a special occasion. A bottle of scouring drops—eighteenth-century spot remover—purchased in 1769 pegs her as a frugal housewife, intent on removing stains from costly silk or wool.

|

Mary Morris gave birth to three girls and two boys between 1761 and 1770, and a handful of purchases relate to them. The first such acquisition, a pair of girls' colored lambskin mitts (fingerless gloves worn by girls and women) was made on September 14, 1767. Presumably Mary bought them for her oldest child, six-year-old Joanna (nicknamed Nancy).

A pair of girls' black gloves purchased in May 1768 was probably destined to Nancy, too, since the Morris's second daughter, Margaret, had died in 1766 at the age of two, and their third, Maria, born in 1765, was only about three years old. Soon, however, Mary was shopping at Deall's for both Nancy and Maria: she bought seven pairs of girls' white worsted wool stockings and a pair of girls' lambskin gloves in 1769, and four pairs of children's colored mitts in July 1771. |

|

Boys' stockings and gloves were available at the shop, too, but none of Mary Morris's clothing purchases relate to her sons—Amherst, born in 1763, and Henry Gage, born in 1770—unless a pair of unspecified children's gloves acquired in 1774 was meant for one of the boys. However, they and their sisters could have enjoyed building towers with the playing cards their mother bought, typically two packs at a time. Larger purchases—eight packs of playing cards on December 13, 1769, and six on January 28, 1774—probably signaled forthcoming adult parties.

|

More prosaically, Mary purchased dry mustard, usually a pound at a time, and occasionally a quart of oatmeal for the larder. On two occasions she carried home a chamber lamp. Such lights, which had a handle on one side so they could be carried upstairs, were designed for use in bedrooms (i.e., bed chambers). A saucer base served the double purpose of making them freestanding and capturing unburned oil that dripped from the wick. Abigail Adams, living in London in 1787, was happy to find chamber lamps that would burn throughout the night on a very small amount of oil—a comment that suggests they were used sometimes as nightlights and not just when undressing or reading in bed.

On arising Mary could have neatened her hair with a "fine ivory comb" purchased in 1771. Then she or a family member might have pulled on warm undergarments made from white flannel. She purchased three and a half, five, and three yards of the fabric, respectively, in October 1766, October 1767, and November 1768. A British cartoon that pokes fun at women outfitting British soldiers in flannel itemizes typical items made from the cloth: caps, chin pieces, waistcoats, drawers, trousers, stockings, socks, and mitts.

One can only hope that the fully equipped man on the right is not called to active duty. He is so heavily enveloped in flannel that he is scarcely able to move, and has not yet put his uniform on top. William Dent, Beauty's Donation or Feeling and Loyalty, 1793. Hand-colored etching. British Museum, 1876,1014.35.

Mary Morris's purchases from Samuel Deall became infrequent after 1771. In '73, for example, she bought only a box of dentifrice, leaving us with no clues to the clothing she must have assembled for twelve-year-old Nancy, who sailed in June to attend school in England under the escort of General and Mrs. Gage. Of course, Deall could not have been the only merchant Mary Morris patronized when shopping for herself and her family. Thus we have only a partial and fragmentary record of her as a consumer. But sometimes furbelows and foodstuffs, hosiery and housewares can illuminate the past like the little flame of a chamber lamp: revealing not grand voyages, gory battlefields, or tottering governments, but rather the cozy, domestic spaces where much of human life is passed.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, December 16, 2016

Note on the Sources: Samuel Deall's account book is in the collection of the New York Public Library, MssCol NYGB 18226. Although it is cataloged as having belonged to an unidentified dry goods merchant, I was able to identify its author as Samuel Deall by examining items advertised in the New York City newspapers of the 1760s and 1770s. Among sellers of fashionable trimmings, Deall was unique in having a small sideline in garden seeds, sales of which are noted in the account book. The names and year of birth of four of the Morris children and the date of Nancy's departure for England are provided by Constance Greiff in The Morris-Jumel Mansion: A Documentary History (Rocky Hill, NJ: Heritage Studies, Inc., 1995), 23–24, 40. The existence of the Morris's third child, Margaret, and the date of her death have not been signaled previously in the modern literature on the family. They are revealed in an 1809 Deed of Release for certain land in Putnam County that had once belonged to the Morrises, the deed having been transcribed into the court record of a late-nineteenth-century case in New York Supreme Court. See In the matter of the application of Allan Campbell, as Commissioner of Public Works of the City of New York, to acquire lands in Putnam County for [a] Storage Reservoir, etc. The Tilly Foster Iron Mine . . . (New York: Martin B. Brown, 1884), 2:1169. Abigail Adams's references to chamber lamps appear in letters she wrote to Mary Smith Cranch (March 8, 1787) and Elizabeth Smith Shaw (March 10, 1787), available at www.masshist.org). The background information on the men's silk stockings illustrated in the photograph comes from the Collections Database, Five Colleges and Historic Deerfield Museum Consortium.