Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion–Part 1:

Investigating an Open and Closed Case

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, and part 8.

|

When I give tours as a docent at the Morris-Jumel Mansion—Eliza Jumel's former home—someone in almost every group asks the same question: Did this house once have shutters? The inquiry is prompted by the remains of hardware on either side of each window designed to hold shutters in an open position. Up until now, my answer has been simple. I explain that shutters were added to the house in the twentieth century because they were thought appropriate to a Colonial-era home, but were removed subsequently when it was realized that the house wasn't designed to have exterior shutters. Instead it had (and still has) folding interior shutters, typical of elegant New York homes of the eighteenth and nineteenth century.

|

|

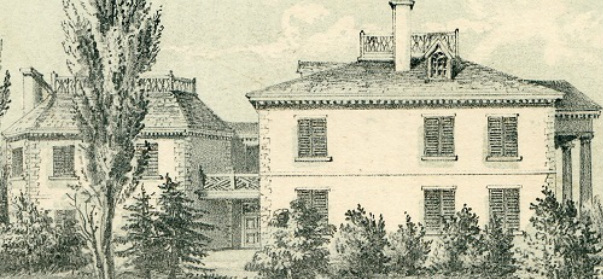

Recently I discovered that the history of the window treatments at the mansion was more complex. My investigation was prompted by the best-known nineteenth-century image of the house, a lithograph made in 1854. In it, the windows of the house are closed by what are sometimes assumed to have been shutters added by Eliza Jumel sometime after she and her first husband Stephen acquired the mansion in 1810.

|

|

But the idea that these structures were shutters has never been convincing to me. They fit inside the window frame, rather than closing it off from the outside, as shutters would do. Nor can we be looking through the window glass at the interior shutters in closed position, because the folding shutters are not slatted. The window treatments in fact look more like venetian blinds. But surely venetian blinds could not have been an original element of a house built in 1765—or could they?

|

Last week I decided to investigate the matter further. I was fascinated to learn that not only have slatted blinds been recorded in civilizations going back to ancient Egypt but also that they became quite popular in the eighteenth century. As early as 1767, an artisan in Philadelphia advertised "Venetian sun blinds for windows," which could be stained any color and moved to any position. In 1761 venetian blinds were installed in Philadelphia's St. Peter's Church (T. L. Purvis, Colonial America to 1763, 1999, p. 49) and by December 1790 fifteen venetian blinds had been completed for the rooms used by the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives in the Philadelphia building called Independence Hall today (T. Fariss, The Romance of Old Philadelphia, 1918, p. 104). When William Bingham of Philadelphia's belongings were sold off in 1805, his elegant parlor contained venetian blinds along with a harpsichord and ten mirrors (Memorial History of the City of Philadelphia, ed. J. R. Young, 1898, 2:70n1).

|

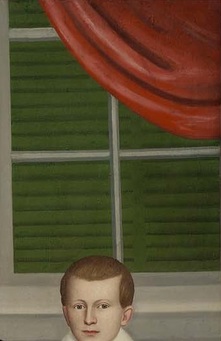

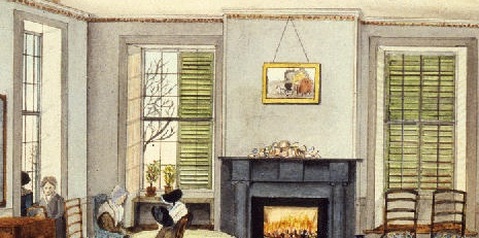

Venetian blinds coexisted with interior shutters. The folding interior shutters kept homes warm in winter, shutting out cold drafts. The blinds, in contrast, let in light and air in the warmer months, while still preserving privacy. They were available in both shadelike and shutterlike styles. The first type could be drawn up to expose the window to a greater or lesser extent, like today's mini-blinds, while the second type took the form of paired panels that opened outward. A painting of about 1839 by Erastus Salisbury Field shows the first type of blind. The canvas tape affixed to the slats and painted to match them provided the flexibility that allowed the blind to be raised. Note that the blinds were hung outside the window rather than inside it; this was common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Click here to see the rest of the painting on the website of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

|

|

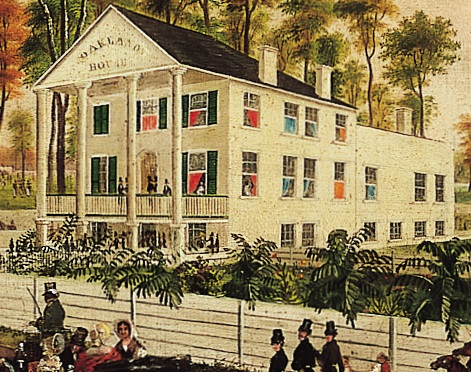

The shutter-type version of venetian blinds appear in a picture painted in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1840. Such blinds (occasionally also called venetian shutters) were hung on the exterior of a building and fit within the window surround when closed. Only the front of this building was equipped with blinds, possibly because privacy was not as much of a concern in the rooms that did not front on the road. The blinds are open on three windows, half open on one, and closed on another. You can admire the complete painting on the museum's website by clicking here.

|

|

A detail of an 1848 watercolor by Joseph Shoemaker

Russell, owned by the New Bedford (MA) Whaling Museum, shows

how shutter-type venetian blinds look from the interior of a room. The appearance of the left window on the fireplace wall makes it clear that the blinds are installed on the outside of the house. We see the closed half of the blind through eighteen small glass panes, which are separated by muntins (narrow horizontal and vertical pieces of wood that hold the panes in place). The other half of the blind cannot be seen; it must be pushed back against the exterior of the building. To see the watercolor as a whole on the museum's website, click here and then on the small icon of the artwork.

|

|

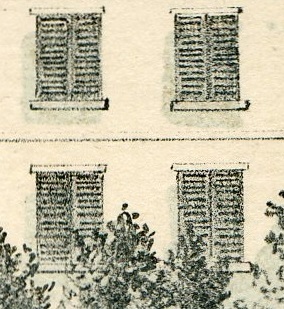

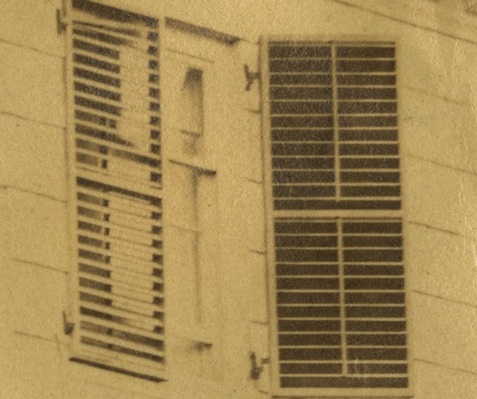

The slats of shutterlike venetian blinds could be fixed or movable. A detail of the exterior of the Morris-Jumel Mansion circa 1860, from a photograph in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, reveals that the mansion indeed had shutter-type venetian blinds and that their slats were fully adjustable. The upper and lower panes of the blinds had separate tilt rods (seen running vertically down the center of the open blind shown here) so that the slats could be slanted at different angles on the upper and lower halves. This feature would have been particularly useful on the

first floor of the house, where the slats could be closed for privacy on the

lower half of the window and left fully open for light and/or air on the upper

half. Only a few inches of this window are cracked open, suggesting that the

weather was mild but not blisteringly hot. Alternatively, the windows may have

been open just enough to let air circulate during the heat of the day,

while protecting the interior from the hottest temperatures.

|

A related practice is described in an article on venetian blinds in The Magazine Antiques by Elisabeth Donaghy Garrett (August 1985). She quotes informatively from the journal of a traveler, Isaac Weld, who visited Philadelphia in June 1796, when the city experienced temperatures in the nineties. Residences were kept so dark during the heat of the day that you could barely see who was present, Weld wrote, adding that "the best houses" were equipped on the exterior of the windows and hall doors with venetian blinds "made to fold together like common window shutters." Homeowners who had such blinds "constantly kept them closed, and the windows and doors were open behind them to admit air." In the Morris-Jumel Mansion's window, a curtain appears to have been drawn partly across the opening to block the sun on the side where the blind was fully opened. The interior shutters may even be closed on that side as well. The triple protection recalls Harriet Beecher Stowe's bemusement that American homes had "three distinct sets of fortifications against the sunshine . . . first, outside blinds; then, solid, folding, inside shutters; and lastly, heavy, thick, lined damask curtains, which loop quite down to the floor"(House and Home Papers, 1865, quoted in Garrett's article).

The original color of the mansion's blinds is conjectural. In 1881 a visitor reported them to be green (although referring to them as "shutters") (Boston Herald, December 25, 1881, p. 9). The New-York Historical Society's photograph of around 1860 reveals that the blinds on both the front of the house and lower story of the east façade were darker than the house itself, which was painted white. Hence those blinds may have been green by 1860 or before. However, the blinds on the upper story of the east façade of the mansion appear to have white exteriors (see the detail below). This coloration, matching the outside of the residence—which, with its white paint, mimics an elegant stone structure—may reflect the aesthetic choice of Roger and Mary Morris, who had the home built in 1765. These particular blinds were above an arbor that abutted the lower story of the house in the Jumel era (1810–1865), so they would have been nearly impossible to reach with a ladder and might not have been overpainted. It is possible, therefore, that they bear witness to the original paint color, and that all of the house's blinds were originally white. This theory is not inconsistent with the lithograph of the house in 1854 with which I began this investigation. Although the image is monochrome, the way the slats are drawn suggests that the artist may have been trying to convey that they were light in color.

The original color of the mansion's blinds is conjectural. In 1881 a visitor reported them to be green (although referring to them as "shutters") (Boston Herald, December 25, 1881, p. 9). The New-York Historical Society's photograph of around 1860 reveals that the blinds on both the front of the house and lower story of the east façade were darker than the house itself, which was painted white. Hence those blinds may have been green by 1860 or before. However, the blinds on the upper story of the east façade of the mansion appear to have white exteriors (see the detail below). This coloration, matching the outside of the residence—which, with its white paint, mimics an elegant stone structure—may reflect the aesthetic choice of Roger and Mary Morris, who had the home built in 1765. These particular blinds were above an arbor that abutted the lower story of the house in the Jumel era (1810–1865), so they would have been nearly impossible to reach with a ladder and might not have been overpainted. It is possible, therefore, that they bear witness to the original paint color, and that all of the house's blinds were originally white. This theory is not inconsistent with the lithograph of the house in 1854 with which I began this investigation. Although the image is monochrome, the way the slats are drawn suggests that the artist may have been trying to convey that they were light in color.

Regardless, the blinds are long gone today, casualties of age. Their replacements can be seen in a 1903 postcard (the same image that appears on the cover of my biography of Eliza Jumel). The stand-ins are similar to the originals, but have wider borders at their bases. Minor differences in the width of the borders and the placement of the dividers between the upper and lower sections suggest that individual blinds may have been replaced in a piecemeal fashion, as dictated by their condition.

|

Yet another transformation in the mansion's window treatments occurred sometime before World War II, as is shown in a photograph from 1936. The blinds are still those recorded in the 1903 postcard (or at a minimum close copies), but a metal shutter dog has been installed on either side of each window to hold the blinds open. As a result, they have the appearance of shutters that are meant to be left open as a decorative element of the façade, rather than blinds adjusted over the course of the day to modulate the lighting of the interior.

|

Today, of course, the house has neither shutters nor blinds. It remains to be seen whether either may reappear at some future time. But at least I feel better prepared to answer when the next visitor inquires about the mysterious shutter dogs that protrude from Eliza Jumel's historic former home.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, February 10, 2016