Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion–Part 4:

The Wallpaper Speaks

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel.

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 1, part 2, part 3, part 5, part 6, part 7, and part 8.

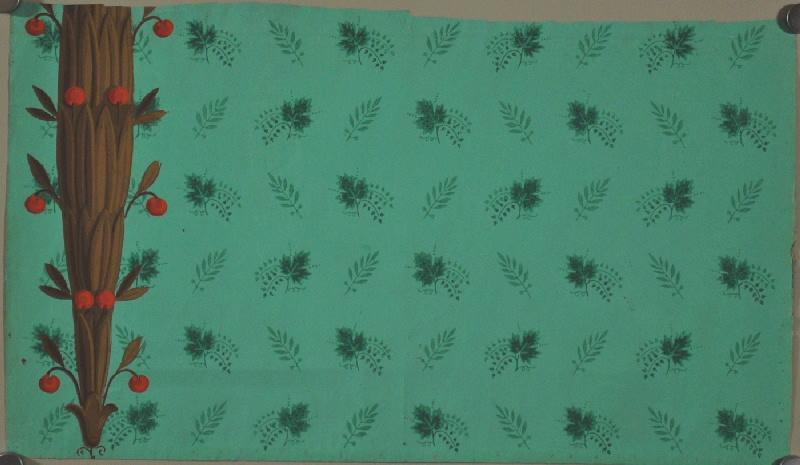

One of the treasures of the Morris-Jumel Mansion is a swath of elegant green wallpaper that once ornamented the octagon room of that historic home. The precious remnant hangs in the upstairs hallway of the house, carefully framed and protected behind glass. Two weeks ago, visiting the mansion while some redecoration work was going on, I found the glass temporarily removed. It was the perfect moment to take some photographs, admire the craftsmanship, and think seriously about when the wallpaper might have been made.

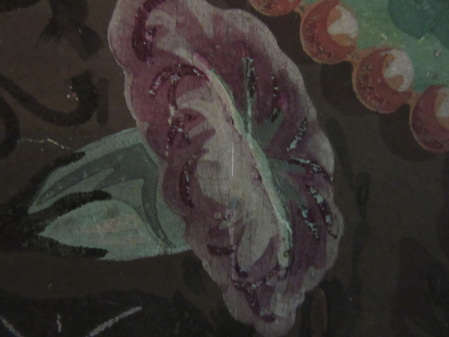

The Morris-Jumel wallpaper has three sections that were printed separately: a lower border, an upper border (also known as a frieze), and a sidewall (the term used to refer to the area between the top and bottom borders). On the lower border, doves drink from fanciful fountains within semicircles outlined by orange beads. Alternating with the areas occupied by the birds are compartments enclosing morning glories that sprout symmetrically from centrally placed stems.

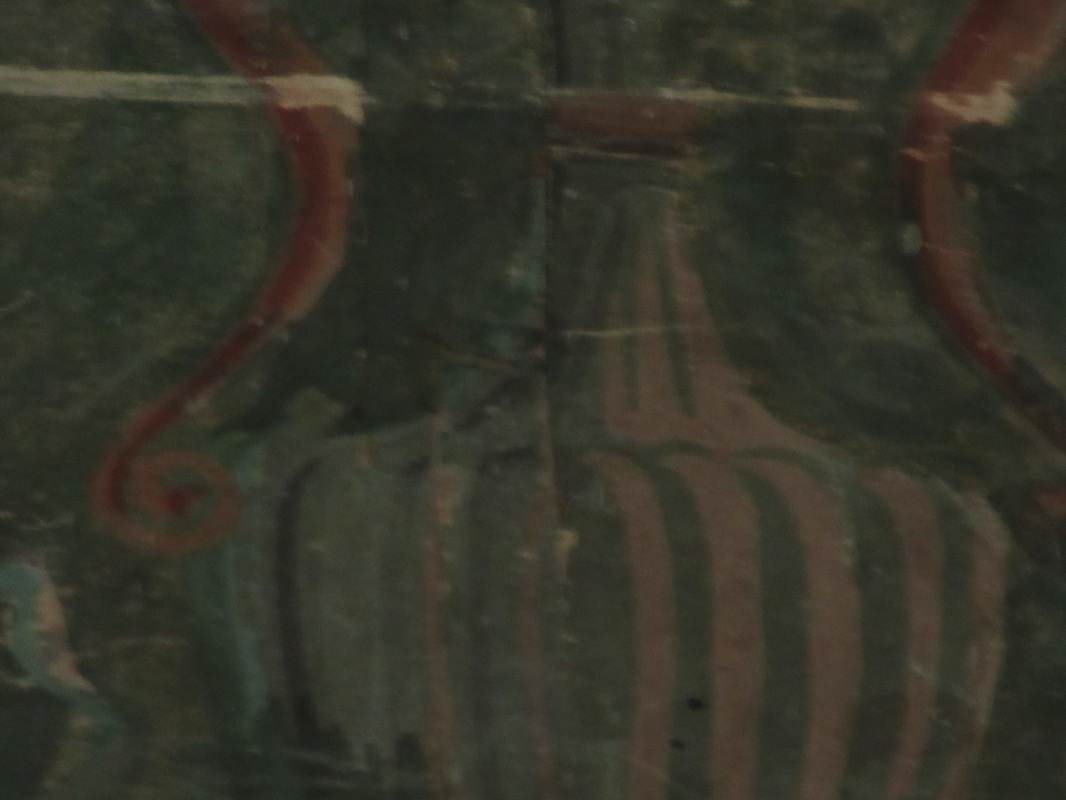

The frieze features pairs of doves, too—this time back to back, separated by a vase, and supporting swags of familiar orange beads. They are contained in triangular compartments that alternate with triangles filled with more morning glory leaves and flowers.

The green sidewalls are block-printed with stylized daisies in a darker shade of green. Areas of daisies are divided vertically by bands of tulips and morning glory vines that “grow” from the lower to upper border.

|

The wallpaper is made of rectangles of paper that were pasted together on their short ends to form strips before the pattern was printed. As you can see in the photograph at right, the design continues without breaks over the seams. The use of joined paper dates this wall covering to before the mid-nineteenth century. Machines to print wallpaper in continuous rolls without seams began to be used commercially in the early to mid-1830s in France, Britain, and the United States, although joined papers continued to be produced into the 1840s in France and 1850s in England.

|

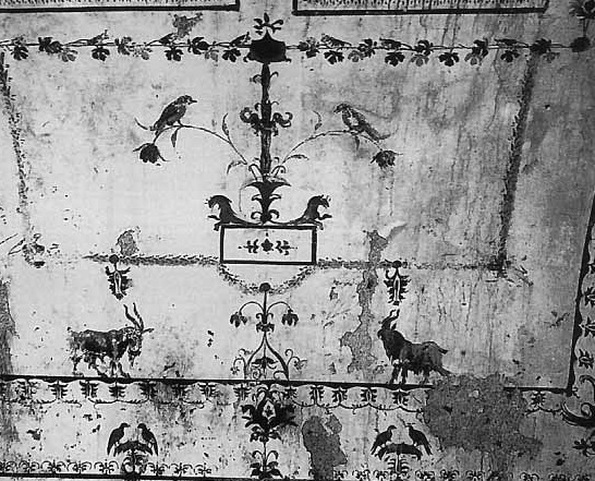

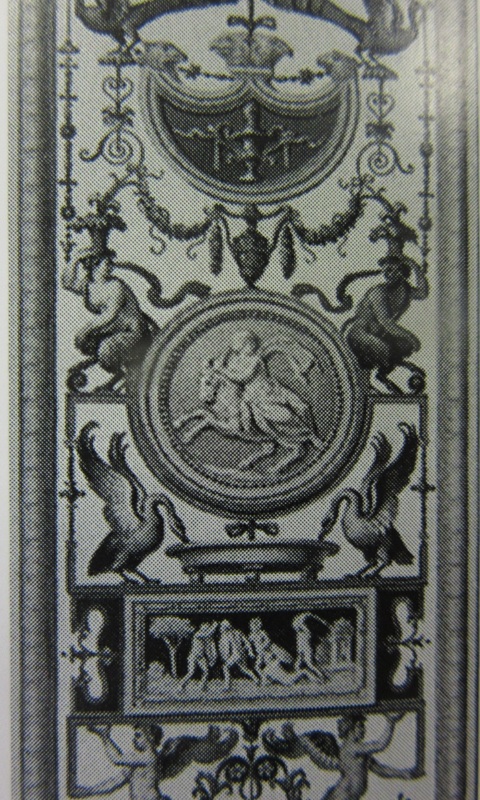

Stylistic analysis further narrows the window of time during which the wall covering could have been manufactured. The vases, swags of beads, and pairs of birds derive from a type of ornamental painting used by the ancient Romans and revived in the Renaissance after Emperor Nero's Golden House (Domus Aurea) was rediscovered during archaeological excavations in Rome about 1480. Explorers found that its walls and ceilings were frescoed with a wealth of fantastic motifs. Animals, monsters, tiny landscapes in frames, masks and medallions, floral and foliate forms were arranged symmetrically around central axes: plant or chandelier stems rising from plinths, vases, or corollas (the cup shape formed by the petals of a flower). The motifs characteristic of this style became known as grotteschi in Italian and "grotesques" in English from the so-called grotte (grottoes) in which they were found. (Nero’s palace was covered by centuries of rubble, so visitors descended into the rooms as one might into a grotto.) The French refer to the forms as arabesques.

|

Whatever they are called, these decorative motifs found immediate popularity in the hands of Italian Renaissance artists, above all Raphael, who used them in decorating the Vatican Loggia (1517–19).

|

|

The style spread quickly across Europe. Grotesques ran riot over walls, ceilings, and textiles in the sixteenth century and then enjoyed renewed popularity in the eighteenth. About 1780 they began to appear on French wallpapers, becoming all the rage. The vogue lasted into the mid-1790s. If by the end of the decade, grotesques no longer occupied the entire surface of wallpaper, they still appeared in borders and decorative compartments. Isolated motifs borrowed from the grotesque style remained popular on wallpaper well into the nineteenth century.

|

Two leading French manufacturers of wallpaper in the late 1780s and early 90s, the Réveillon factory and the firm of Arthur et Robert, used motifs that could have inspired the designer of the Morris-Jumel wallpaper.

|

A firm known as Jacquemart et Bénard rented and then purchased the Réveillon factory in 1791–92. The partners (and later Jaquemart's sons) continued to employ many of the designs of their predecessor but also developed original compositions. From 1799 Jacquemart et Bénard experimented with repeating floral ground patterns that drew their inspiration from textiles.

|

|

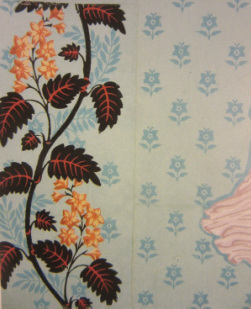

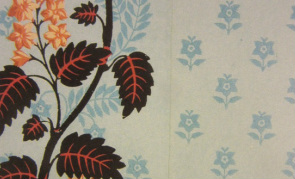

An early nineteenth-century Jacquemart et Bénard wallpaper combines a trailing vine with a textilelike ground bearing a simple floral motif. The composition is suggestive of the pairing of morning glory vines and fields of daisies on the Morris-Jumel wallpaper. The leaves and stems of the vine appear to have a flocked surface, like those of the Morris-Jumel morning glories. This wallpaper may have had a figural component. The pink form at right could be the trailing edge of a skirt.

|

A floral-pattern Jacquemart et Bénard paper dating from about 1808 has a green ground like the Morris-Jumel paper. The color was particularly popular in wallpaper of the first quarter of the nineteenth century. As on the Morris-Jumel wallpaper, a vertically oriented motif divides areas printed with the floral pattern.

|

There isn't a precedent for a sidewall containing both a Morris-Jumel-type morning glory vine and a floral ground pattern in the documented production of Jacquemart et Bénard or their contemporaries. However, a border decorated with a morning glory appears in a wallpaper sample book dating from ca. 1785–95 that was used by the Réveillon factory and/or Jacquemart et Bénard (it is unclear whether the book predates or postdates Jacquemart et Bénard's takeover of the business). It is interesting to compare the vine to that on the Morris-Jumel Mansion wallpaper. Aside from the difference in palette (blue, black, and tan versus pink and green), the chief feature distinguishing the two papers is the striking three-dimensionality of the example in the sample book. The leaves cast shadows and the stem of the vine appears to be growing just above the neutral ground. In contrast, the designer of the Morris-Jumel vine focused on achieving a decorative surface without breaking the picture plane.

|

A wallpaper frieze that falls about halfway between the three-dimensionality of the Réveillon border and the linear, decorative qualities of the Morris-Jumel vine once hung at Montgomery Place in Annandale-on-Hudson (about one hundred miles north of New York City). It features a vine with flocked black leaves and white blossoms. Possibly the plant is meant to be a moonflower, a morning glory with white flowers that open at night.

This frieze and the striped paper it bordered were the earliest wallpapers hung in the parlor at Montgomery Place. As the estate was purchased in 1802 and the house completed three years later, the border and sidewall can be dated to ca. 1805. |

How does the information gathered here relate to the dating of the Morris-Jumel Mansion morning glory wallpaper?

These findings lead to the following conclusions:

It is not clear who manufactured the wallpaper. Given its design and quality, it was certainly made in France, the source for most wallpapers imported to the United States in the early nineteenth century. The firm of Jacquemart et Bénard is a possibility, but not a wholly convincing one. The papers from this factory show a consistent concern for three-dimensionality, frequently to the point of employing trompe l'oeil effects. Occasionally a stronger priority is given to surface pattern. The wallpaper of 1805–1814 with the flocked vine and ground of stylized blue flowers is one of those rare exceptions. Certainly it is the closest to the Morris-Jumel paper. But even in that case a touch of three-dimensionality is incorporated by placing the vine over a foliate pattern printed in light blue.

- It must have been made after 1780, because it employs motifs known as grotesques or arabesques that did not appear on wallpaper until the beginning of the 1780s.

- The grotesque elements are confined within the lower border and frieze rather than distributed over the sidewall, suggestive of a nineteenth-century rather than eighteenth-century origin. But their pastel colors, soft contours, and touch of whimsy look back to the eighteenth century rather than forward to the nineteenth, with its harder forms and archaeological exactitude. They are unlikely to date much beyond 1810.

- The sidewall has a ground of small floral motifs punctuated with vertical dividers (the morning glory vines). This combination of elements (although not the use of morning glory vines for the verticals) is seen on securely dated Jacquemart et Bénard wallpapers made from 1803 to 1805 (e.g., this from 1803, this also from 1803 , and this from 1805). Use of the style may have continued as late as 1814: the two examples I reproduced were dated 1805–1814 and circa 1808, respectively (probably based on stamps or markings used by the factory, although those who dated them did not explain their rationales).

- The morning glory vine on the sidewall is related, although not identical, to a vine that appears on a French wallpaper hung in New York State ca. 1805.

These findings lead to the following conclusions:

- The wallpaper was made no earlier than 1803, as the layout and ground pattern of the sidewall derive from a style introduced by Jacquemart et Bénard in that year.

- It was made no later than 1814 and probably no later than 1810, given elements that are holdovers from the eighteenth century (especially the handling of the grotesques).

It is not clear who manufactured the wallpaper. Given its design and quality, it was certainly made in France, the source for most wallpapers imported to the United States in the early nineteenth century. The firm of Jacquemart et Bénard is a possibility, but not a wholly convincing one. The papers from this factory show a consistent concern for three-dimensionality, frequently to the point of employing trompe l'oeil effects. Occasionally a stronger priority is given to surface pattern. The wallpaper of 1805–1814 with the flocked vine and ground of stylized blue flowers is one of those rare exceptions. Certainly it is the closest to the Morris-Jumel paper. But even in that case a touch of three-dimensionality is incorporated by placing the vine over a foliate pattern printed in light blue.

It seems most likely that the Morris-Jumel Mansion wallpaper was made by a different firm, but one that drew inspiration from Jacquemart et Bénard's designs. I suggest, therefore, the following attribution: Circle of Jacquemart et Bénard, ca. 1803–1810.

There is one further matter to consider: who bought the paper and had it installed?

The house today known as the Morris-Jumel Mansion was purchased in 1799 by a British merchant named Leonard Parkinson. Then in 1810 it was offered for sale and acquired by Eliza and Stephen Jumel. It is possible that the wallpaper was hung during Parkinson's tenure. But it is unclear if he ever inhabited the house himself. By 1805 he was the sheriff of Herefordshire, in England, and he appears to have remained in England until his death in 1817. He may have acquired the property as an investment. When he sold it, the paperwork was handled by his New York-based son, also named Leonard Parkinson. The younger Leonard could have used the house and decorated it. However, there are no records of him having resided there.

With more certainty, we know that the Eliza and Stephen Jumel furnished the house after acquiring it in April 1810. The odds are good that it was they who purchased and hung the morning glory paper around 1810 or 11. As it still decorated the walls of the octagon room of the mansion at the time of Eliza Jumel's death in 1865, it was certainly in the mansion throughout the years they lived there, whether they purchased it shortly after acquiring the house or found it on the walls when they arrived.

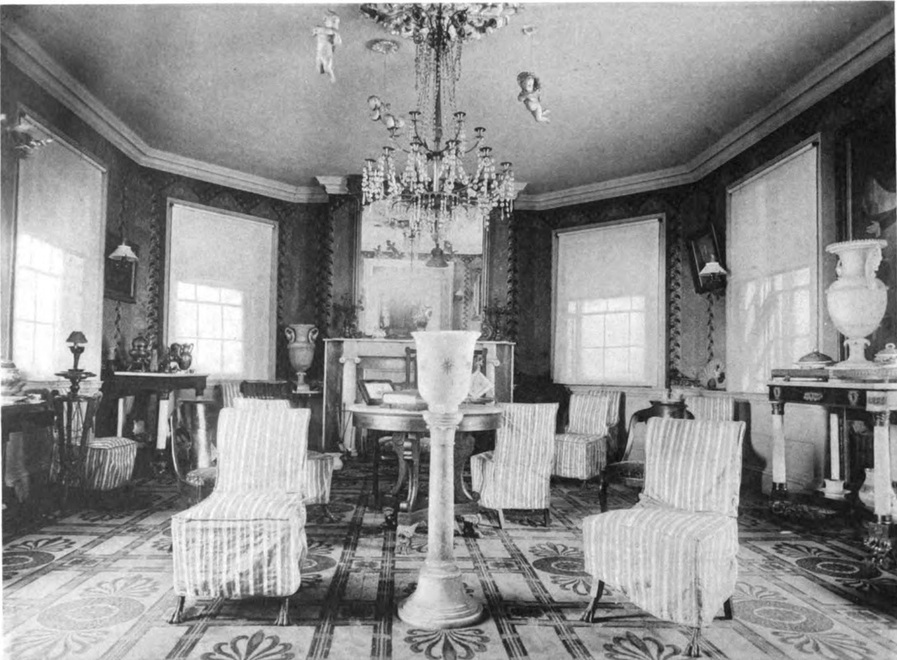

Appropriately, a reproduction of this historic paper decorates the house today, although it hangs in the front parlor rather than the octagon. Together with furniture that Stephen and Eliza owned, it helps us envision their early nineteenth-century world.

There is one further matter to consider: who bought the paper and had it installed?

The house today known as the Morris-Jumel Mansion was purchased in 1799 by a British merchant named Leonard Parkinson. Then in 1810 it was offered for sale and acquired by Eliza and Stephen Jumel. It is possible that the wallpaper was hung during Parkinson's tenure. But it is unclear if he ever inhabited the house himself. By 1805 he was the sheriff of Herefordshire, in England, and he appears to have remained in England until his death in 1817. He may have acquired the property as an investment. When he sold it, the paperwork was handled by his New York-based son, also named Leonard Parkinson. The younger Leonard could have used the house and decorated it. However, there are no records of him having resided there.

With more certainty, we know that the Eliza and Stephen Jumel furnished the house after acquiring it in April 1810. The odds are good that it was they who purchased and hung the morning glory paper around 1810 or 11. As it still decorated the walls of the octagon room of the mansion at the time of Eliza Jumel's death in 1865, it was certainly in the mansion throughout the years they lived there, whether they purchased it shortly after acquiring the house or found it on the walls when they arrived.

Appropriately, a reproduction of this historic paper decorates the house today, although it hangs in the front parlor rather than the octagon. Together with furniture that Stephen and Eliza owned, it helps us envision their early nineteenth-century world.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, June 9, 2016.