Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion–Part 3:

Mme. Jumel Redecorates: A Woman and Her Furniture

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 1, part 2, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7 and part 8.

|

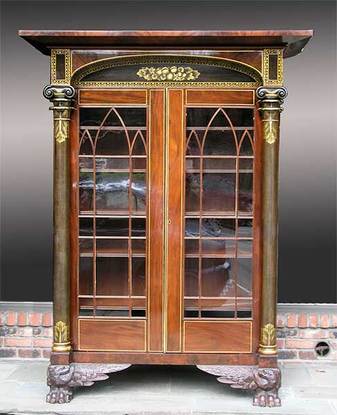

Several years ago, not long after beginning to volunteer as a docent at the Morris-Jumel Mansion, I spent a Saturday evening at the Metropolitan Museum. Strolling through the American Wing, I noticed a handsome secretary-bookcase (a piece of furniture combining bookshelves with a pullout or fold-down writing surface) that reminded me of a pier table at the mansion. The capitals of the columns on the pier table and those on secretary-bookcase sported the same deeply carved volutes (scrolls) and alternating short and tall acanthus leaves.

|

|

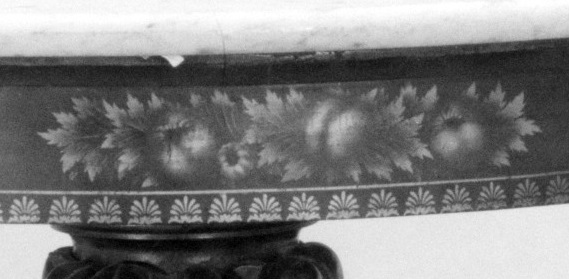

Bookcase and table had similar feet, decorated with acanthus leaves above the paws on the front façade and drapery swags above the paws on the side façade. The lower edge of both pieces of furniture was ornamented with gilded cornucopias filled with apples, peaches, and deeply lobed melons. The stenciled decoration on each piece included a repeating motif of linked circles, with a gold line above and below the interlocked band.

There were small differences: the top edge of the cornucopia, smooth on the secretary-bookcase, was formed from the ends of leaflike elements on the pier table. The drapery on the outer side of the paws was stretched in horizontal bands on the secretary-bookcase and on the pier table hung more naturalistically. The cornucopia and paw details appeared to have been carved by different hands, although the two pieces of furniture could have come from the same workshop.

I noted the similarities and differences for future investigation, but put the project aside to delve into Eliza Jumel's convoluted life history. Then in late December, after a gap of four years, I came upon the secretary-bookcase once more. The striking similarities between it and the Morris-Jumel pier table prompted me to resume my long-neglected research. How did these pieces relate to each other? Were there other "relatives" at the mansion or elsewhere? Who made them, and when?

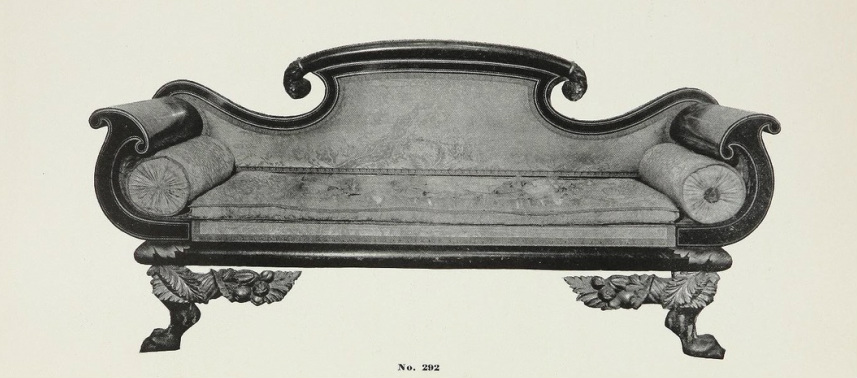

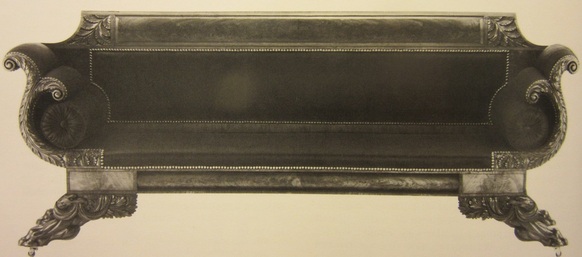

Very quickly I spotted a probable cousin right in the front parlor of the Morris-Jumel Mansion. A sofa owned by Eliza Jumel—even mentioned in the inventory at the time of her death—sports a carved and gilded cornucopia bearing the same selection of fruit as the two pieces of furniture mentioned previously. On all three items, the cornucopias and their contents have a gravity-defying quality, jutting out unsupported to terminate in a large acanthus leaf. The paw feet of the sofa, with their sturdy toes and prominent knuckles, resemble the paw feet on the other two pieces.

I noted the similarities and differences for future investigation, but put the project aside to delve into Eliza Jumel's convoluted life history. Then in late December, after a gap of four years, I came upon the secretary-bookcase once more. The striking similarities between it and the Morris-Jumel pier table prompted me to resume my long-neglected research. How did these pieces relate to each other? Were there other "relatives" at the mansion or elsewhere? Who made them, and when?

Very quickly I spotted a probable cousin right in the front parlor of the Morris-Jumel Mansion. A sofa owned by Eliza Jumel—even mentioned in the inventory at the time of her death—sports a carved and gilded cornucopia bearing the same selection of fruit as the two pieces of furniture mentioned previously. On all three items, the cornucopias and their contents have a gravity-defying quality, jutting out unsupported to terminate in a large acanthus leaf. The paw feet of the sofa, with their sturdy toes and prominent knuckles, resemble the paw feet on the other two pieces.

The top rail and arms of the sofa are outlined with a gold border consisting of a thick outer line and thin inner line, a motif that appears in several places on the secretary-bookcase. Although the sofa cornucopia takes a slightly different form than those on either of the other two pieces—its top edge is scalloped and its body ornamented with shallow troughs rather than the ridges of the secretary-bookcase or quasifoliate forms of the pier table—the distinctions are small enough to suggest the hands of a craftsman within the same workshop.

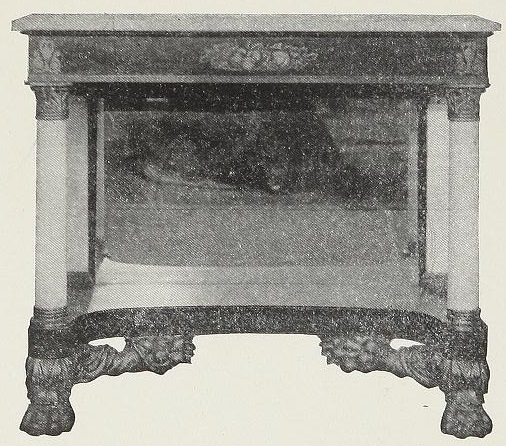

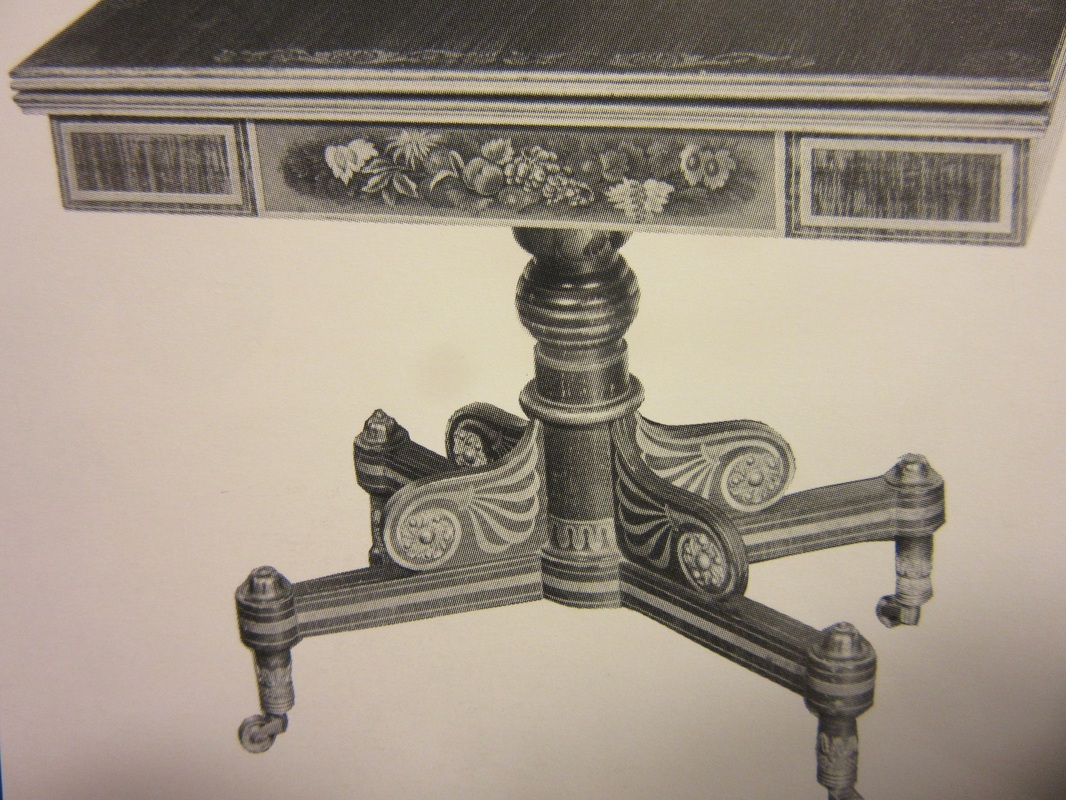

Another piece of Eliza Jumel's furniture seems to belong to the family, too. It's a pier table (if you were wondering, that's a piece of furniture designed to stand against a pier, the space between two windows). I’ll call it pier table 2 to distinguish it from the table discussed previously (hereafter pier table 1). Eliza Jumel's great-niece, Eliza Jumel Caryl, inherited it along with other furniture once owned by her great aunt. When she died in 1916 and her Jumel possessions were auctioned at Silo's Fifth Avenue Art Galleries, pier table 2 rated one of the few illustrations in the catalogue. It is known today only from this photograph.

On it we find two cornucopias that almost seem to float on air, extending from a pair of familiar paw feet. The horns of plenty are closest to those on the Metropolitan Museum's secretary-bookcase, although wrapped in a twist of drapery rather than being overlain with acanthus leaves and terminating with stubby rather than gracefully extended foliage. The table apron is stenciled with fruit and leaves in the center, like the pediment, columns, and table apron of the secretary-bookcase, and has classical urns stenciled at either end.

Pier tables 1 and 2, the sofa, and the secretary-bookcase incorporate related elements, but combine them in different ways. Was it coincidence or a real relationship? Expanding my hunt, I tracked down twelve pieces of furniture that seem to form an extended family together with the four just discussed. Besides the presence of fruit-filled cornucopias, they display one or more of the features already examined: the linked circle motif, the thick-thin parallel stripes, the distinctively formed paws, the drapery swag on the outer sides of the front feet, and the capitals with deeply carved volutes and short and tall acanthus leaves. These features, simple as they may seem, are not common on New York furniture from the 1820s and early 1830s, and instead appear to be characteristic only of this group. Here are the family photographs.

Pier tables 1 and 2, the sofa, and the secretary-bookcase incorporate related elements, but combine them in different ways. Was it coincidence or a real relationship? Expanding my hunt, I tracked down twelve pieces of furniture that seem to form an extended family together with the four just discussed. Besides the presence of fruit-filled cornucopias, they display one or more of the features already examined: the linked circle motif, the thick-thin parallel stripes, the distinctively formed paws, the drapery swag on the outer sides of the front feet, and the capitals with deeply carved volutes and short and tall acanthus leaves. These features, simple as they may seem, are not common on New York furniture from the 1820s and early 1830s, and instead appear to be characteristic only of this group. Here are the family photographs.

On all twelve items, the cornucopias are draped at the narrow end with acanthus leaves or swags of cloth and terminate at the opposite end with foliage (typically stubby but occasionally longer and more graceful). They all have paw feet, with drapery swags discernible on the sides on I and K (the sides of the feet are not visible in the other photographs). Eight tables have the capitals with carved scrolls and acanthus leaves of alternating heights. Five (D, E, G, I, and L) feature the linked circle motif (it is not visible in the photograph of D, but was documented by the conservator who restored the table). Eight tables (A, B, D, E, F, G, H, and L) have fruit and foliage stenciling on their aprons like the Jumel pier table 2, and seven also have floral or gilt decorations at the far ends of their aprons as it does (B, C, D, E, F, G, and H). Three have ormolu (gilded metal) mounts at the center and ends of the apron instead (I, J, K), typically a more expensive option than stenciled decoration. One table (F) has center apron stenciling apparently identical to those on pier table 2 and possibly identical column capitals as well.

In what shop were they made? Before we attempt to answer that question, let us look at another aspect of this cabinetmaker’s production. The clues to identifying a second group of his tables await our discovery at the Morris-Jumel Mansion. After gathering cornucopias—the fruits of the earth—we must take to the air in search of the mighty eagle.

An eagle hunt

Our chase begins with a photograph of the mansion's octagon room taken in the 1880s. On the right side of the room is a piece of furniture that I will dub pier table 3. Some thirty years after this image was made, table 3 was auctioned with the rest of Eliza Jumel's possessions at Silo's Fifth Avenue Art Galleries. Claimed implausibly in the sale catalogue to have come from the Tuileries Palace in Paris, it was said to be made of mahogany with a mirrored back and marble top. Its decoration included "ormolu mounts, typifying the ending of the Egyptian campaign," and "laurel wreaths of victory" (whether ormolu or more probably stenciled and gilded is not stated). Our nineteenth-century photograph shows these details (without clarifying whether the wreaths were ormolu or stenciled), as well as several other features unmentioned in the auctioneer's listing. Just below the plinth we can see an eagle with a drapery swag in its beak and an outstretched wing. Barely visible beneath the other side of the table is a familiar paw foot. It is difficult to pick out the details of the compact column capitals, but they appear to be carved like the capitals of pier table 2 and table F with leaves pointing upwards, their veins forming prominent ridges.

Where this piece ended up after being sold at Silo's is unknown, but the Morris-Jumel Mansion possesses a closely related pier table (hereafter pier table 4). Its paw feet, eagles, and column bases and capitals appear to be identical to those of pier table 3, as do the ormolu mounts on the canted corners of its apron in the form of two griffins flanking an upright lyre. (A griffin has a lion's body combined with an eagle’s head and wings.)

The tables vary in the decoration on the fronts of their aprons. The ormolu mount in the center of table 4 features two sphinxes (half human, half lion and sometimes winged) on a smooth ground line facing an altar or incense burner. The mount on table 3 has a central wreath and an irregular lower border (the photograph is too blurry to pick out the motifs on either side of the wreath). Table 4 can also be distinguished from table 3 because it does not have wreaths above the columns, although perhaps they were damaged and removed. The finish of the table looks paler over the one of the front columns, where a stenciled wreath finished in gold leaf could have been.

In spite of the use of an eagle rather than a cornucopia beneath the plinth, these two tables appear to be members of the family of furniture discussed in the first part of this article. They share the distinctive paw feet and the aesthetic of using ebonized wood (wood finished in black to look like ebony) and veneers of mahogany or rosewood on a single piece of furniture. For example, the Morris-Jumel Mansion pier tables 1 (with a cornucopia) and 4 (with an eagle) both have ebonized plinths but veneered aprons. Another stylistic link between the cornucopias and eagles is that two members of the cornucopia group (pier tables F and 2) have capitals carved in the same way as the tables with eagles (3 and 4).

|

A bookcase currently at the Post Road Gallery in Larchmont, New York, connects the two groups also. It is particularly close to the Metropolitan Museum's secretary-bookcase in its fruit-and-foliage stenciling and mix of ebonized and veneered finishes. However, it rests on eagles like pier tables 3 and 4, although its birds do not clasp drapery swags in their beaks.

Eagles appear to be less common than the cornucopias in this furniture family—a recessive trait, perhaps?—but at least a couple of other examples exist. A card table at Bayou Bend, a house museum operated by the Houston Museum of Art, has the same carved eagles under its plinth and griffin mounts on its canted corners as pier tables 3 and 4, and is finished with both veneered and ebonized surfaces. |

|

|

Even more interestingly, either the Bayou Bend table or what was described as a "virtually identical" table sold at Christie's New York on June 2, 1990 (lot 173) may have been owned by Eliza Jumel. Lot 274 of the 1916 auction of the Jumel collection was a piece grandly labeled "Napoleon's Card Table." It was described as being "inlaid" ("veneered" was meant) in crotch mahogany with ormolu mounts, and having a folding top and four-column pedestal base. The hammer price, $320, was one of the highest in the sale for a single item, suggesting that it was a high-quality piece like the Bayou Bend table. The presence of griffin mounts is also suggestive. Works claimed as "Napoleon's" in the Jumel auction had decoration that could be vaguely associated with the Consulate and First Empire, such as the wreaths and griffins on pier table 3 that were said to relate to the future emperor’s Egyptian campaign (clearly the cataloguer did not distinguish between Greco-Roman griffins and Egyptian sphinxes!). Napoleon's name may have been coupled with this card table or its twin because of their griffin mounts.

|

In search of an attribution

|

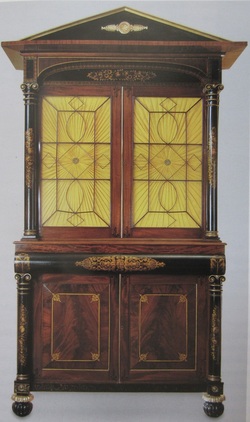

Now that we have a body of furniture with which to work, it is time to circle back to the Metropolitan Museum's secretary-bookcase. In 2000 Catherine Hoover Voorsanger published an image of a strikingly similar piece of furniture, a bookcase signed and dated 1829 by a cabinet maker named Robert Fisher (Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, pp. 293–95 and fig. 239). It had the fruit-and-foliage stenciling, the use of both veneered and ebonized wood, similarly demarcated panes of glass in the doors, and similar stenciled and gilt border motifs. On the basis of the resemblance she noted between it and the unsigned secretary-bookcase at the Metropolitan, today the latter carries the label "Attributed to Robert Fisher."

Others have noted parallels between a handful of the works I have discussed and the Metropolitan's secretary-bookcase (sometimes referring to it as a work by Joseph Meeks, the attribution it carried before it was associated with Robert Fisher). As early as 1991, conservator Cynthia Moyer remarked similarities between the secretary-bookcase and three works she had treated (D and G of the cornucopia group illustrated above, as well as a pier table forming a pair to D) (Gilded wood: Conservation and history, ed. D. Bigelow et al., 1991, pp. 333, 336). More recently, resemblances to the secretary-bookcase were noted when table A was sold at Christie's in 2006 and when table J was formerly with dealer Christopher H. Jones. They have also been observed with regard to table I by the dealer currently offering it for sale. But this is the first time that such a large group of furnishings have been identified as related to the secretary-bookcase and, significantly, to each other. I propose that all of the pieces of furniture I have discussed were made in the workshop of Robert Fisher, or at a minimum by someone who had worked closely with him. |

Robert Fisher: A tale of Baltimore and New York

There are two personalities bearing the name Robert Fisher who are mentioned in the history of nineteenth-century American furniture. A Robert Fisher who was a "fancy chair maker" (someone who made furniture with elaborate painted decoration) appeared in Baltimore's city directory between 1800 and 1810. As William Voss Elder III has suggested, it was probably this Fisher who moved up in the world to become the Robert Fisher, lumber merchant, listed in the Baltimore directories in 1817 and 1819 (Baltimore Painted Furniture 1800–1840, 1972, pp. 14, 106).

New York also claims a Robert Fisher, documented like his alter ego only through appearances in the city directories. He was listed as a cabinetmaker from 1824 through 1837, with the exception of 1825; perhaps he missed being included in the directory that year due to one of his frequent changes of address. It is this New York furniture maker who is assumed to have crafted the bookcase dated 1829 and signed "Robert Fisher."

Could these two individuals have been one? The timing of the Baltimore Robert Fisher's disappearance from the city directories is significant. The Panic of 1819 hit the American economy hard. With little demand for wood for furniture making and home construction, a lumberyard like Fisher's would have suffered. Even John and Hugh Finley, Baltimore's best-known cabinetmakers, had to lay off all their workers as the recession set in (Classical Maryland 1815–1845, 1993, p. 100). The appearance of Robert Fisher, cabinetmaker, in New York in 1824 may be an indicator that the chair maker turned lumber merchant had moved north to make a new start.

New York also claims a Robert Fisher, documented like his alter ego only through appearances in the city directories. He was listed as a cabinetmaker from 1824 through 1837, with the exception of 1825; perhaps he missed being included in the directory that year due to one of his frequent changes of address. It is this New York furniture maker who is assumed to have crafted the bookcase dated 1829 and signed "Robert Fisher."

Could these two individuals have been one? The timing of the Baltimore Robert Fisher's disappearance from the city directories is significant. The Panic of 1819 hit the American economy hard. With little demand for wood for furniture making and home construction, a lumberyard like Fisher's would have suffered. Even John and Hugh Finley, Baltimore's best-known cabinetmakers, had to lay off all their workers as the recession set in (Classical Maryland 1815–1845, 1993, p. 100). The appearance of Robert Fisher, cabinetmaker, in New York in 1824 may be an indicator that the chair maker turned lumber merchant had moved north to make a new start.

|

|

A more significant link between the two Fishers is found in the stylistic details of the furniture associated with the New York cabinetmaker. His oeuvre is characterized by features rarely seen previously in New York-made cabinetwork—most importantly the abundant use of stenciled decoration, virtually absent from mid- and high-end furniture in New York before the 1820s. In contrast, Baltimore was known for the elaborate painted and stenciled decoration of its furniture by the beginning of the nineteenth century. Most popular were Greco-Roman motifs derived from pattern books published in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century by connoisseurs and designers including Thomas Hope and George Smith in England and Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine in France. But by the end of the second decade of the nineteenth century, a homegrown imagery of fruits and foliage, drawn freehand or stenciled with powdered bronze, began to appear on high-end Baltimore furniture as well. A table ordered from Baltimore’s Hugh Finley in March 1819 exemplifies the new style, in which naturalistic and neoclassical motifs are used side by side. Such fruit-and-foliage motifs, stenciled with bronze powders on table aprons, are not documented on New York furniture before the mid-1820s. Given their abrupt appearance—possibly first on furniture associated with Robert Fisher (see Appendix)—they could have arrived from Baltimore with him. The carved, gessoed, and gilded cornucopias he placed beneath plinths were also new to New York, as was his generous use of ebonized wood, often contrasted with veneers to create visually dramatic surfaces. Indeed Fisher’s pier tables with ebonized plinths—one of his characteristic furniture types—had no obvious prototypes in New York. Tables with plinths finished in this way were not made by Duncan Phyfe and Charles-Honoré Lannuier, the leading cabinetmakers in early nineteenth-century New York, nor by their faithful copyists such as Michael Allison. In contrast, fancy chairs, like those the Baltimore Fisher crafted as a young man, often featured painted decoration on a black ground; they could have inspired their maker to experiment with ebonized surfaces.

|

|

If Fisher brought new ideas with him from Baltimore, he adopted local fashions as well. In New York he seems to have been most strongly influenced by the work of the French-born Lannuier. For example, the sphinx mounts used on several of his works are slightly simplified versions of mounts that Lannuier used on at least three pier tables (Peter M. Kenny, Honoré Lannuier: Cabinetmaker from Paris, 1998, no. 94, 95, 96).

|

|

On two other pier tables (I and K), Fisher employed ormolu mounts featuring crossed branches of flowers with a wreath in the center, forms that may have been inspired by a mount of crossed rose branches used on a Lannuier card table made in 1817.

|

|

Mounts were imported from Europe, most commonly from Birmingham, England, and were not used exclusively by a single artisan. But Fisher's choice of designs related to those used by Lannuier is interesting. In addition, he seems to have drawn inspiration for some of his stenciled patterns from Lannuier's brass inlays. For instance, the decoration on the top edge of the Metropolitan's secretary-bookcase relates closely to the inlay on the 1817 Lannuier card table. Although the French-born craftsman died five years before Fisher is recorded in New York, the latter could have seen works by Lannuier and met, worked with, or even hired, craftsmen who had worked for him. Indeed Lannuier's workshop was still in business, carried on after his 1819 death by his foreman (Kenny, Honoré Lannuier, 1998, p. 51).

|

|

Other Fisher motifs came from French pattern books (on which Lannuier also drew). For example, a cartouche form that Fisher used to demarcate decorative areas on furniture surfaces was adapted from a design for a wall painting published by Percier and Fontaine. He also drew on frieze patterns from the same plate for his stenciled borders.

|

|

Eliza Jumel and Robert Fisher

|

Eliza Jumel owned a striking number of the works here identified with Robert Fisher. The Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City, her home between 1810 and 1865, possesses at least thirteen such items: pier tables 1 and 4 (given to the mansion by the same donor and said to have been owned by Jumel); the sofa discussed at the beginning of this article; and ten chairs matching the sofa (like it, they are known without doubt to have been hers). Besides these pieces, she owned pier tables 2 and 3 (current locations unknown) and probably a card table decorated with eagles (whether the one today at Bayou Bend or that sold by Christie's in 1990). A plainer card table said to have been hers, today at the Morris-Jumel Mansion, may also belong to the assemblage. It has gadrooned rings—an uncommon feature on New York-made card tables—immediately below the water-leaves that wrap around its four balusters. Such rings appear on at least one labeled table by Lannuier, a possible hint that we should look for the maker of the Morris-Jumel table among cabinetmakers influenced by him. Fisher, as we have seen, would fit that description.

|

When did Jumel acquire this large group of related items? Answering this question requires a quick recap of her biography. In the early 1820s, she and her husband Stephen were living in France. However, the Panic of 1825 had a devastating effect on the couple’s finances. Jumel returned to the United States alone in the spring of 1826, ostensibly to look after their New York real estate and collect funds to send to Stephen.

Their country home, the Jumel Mansion, was in the hands of a tenant who used it occasionally for country parties. Jumel inspected it, noting the need for new wallpaper and repairs to the fences and entryway. In January or early February of 1827, she regained possession of the house and moved in.

There was probably little furniture. Neither she nor Stephen had been in the United States since 1821, and she had auctioned off most of the contents of the house before her departure that year. Half-empty rooms would not have mattered if she were planning to rejoin her husband in France. But gradually it became clear she planned to stay in New York. Not only did she encourage Stephen to return to America, she sent him little or none of the rents she collected from their properties in Manhattan. That raises the question of where the funds went. The most likely explanation is that she spent much of the money on furniture for the residence.

Today the Morris-Jumel Mansion has a remarkable cache of furnishings with a Jumel provenance that appear to date stylistically between the mid-1820s and early 1830s. Besides those items discussed here, there are others awaiting further research; some may be by Fisher also. A redecoration campaign by Jumel in 1827 or, less likely, the first half of 1828, would account for the presence of so many contemporaneously dated works. It would also clarify a matter previously observed but not fully explained: why Stephen's letters to Jumel turned cold by October 1827. He would have had reason to be upset if he learned she had spent money he needed badly on furnishings.

Their country home, the Jumel Mansion, was in the hands of a tenant who used it occasionally for country parties. Jumel inspected it, noting the need for new wallpaper and repairs to the fences and entryway. In January or early February of 1827, she regained possession of the house and moved in.

There was probably little furniture. Neither she nor Stephen had been in the United States since 1821, and she had auctioned off most of the contents of the house before her departure that year. Half-empty rooms would not have mattered if she were planning to rejoin her husband in France. But gradually it became clear she planned to stay in New York. Not only did she encourage Stephen to return to America, she sent him little or none of the rents she collected from their properties in Manhattan. That raises the question of where the funds went. The most likely explanation is that she spent much of the money on furniture for the residence.

Today the Morris-Jumel Mansion has a remarkable cache of furnishings with a Jumel provenance that appear to date stylistically between the mid-1820s and early 1830s. Besides those items discussed here, there are others awaiting further research; some may be by Fisher also. A redecoration campaign by Jumel in 1827 or, less likely, the first half of 1828, would account for the presence of so many contemporaneously dated works. It would also clarify a matter previously observed but not fully explained: why Stephen's letters to Jumel turned cold by October 1827. He would have had reason to be upset if he learned she had spent money he needed badly on furnishings.

|

A slightly later date for the acquisition of the furniture would be possible, but less convincing. Stephen rejoined his wife in the United States in July 1828. He remained concerned about their financial position; it is unlikely that he would have been enthusiastic about spending significant sums updating the interior of the mansion. Although more money was available after his death in 1832, Jumel left New York to escape a cholera epidemic approximately six weeks after his passing and did not return until almost the end of the year. By then styles were in flux. Furnishings made of highly polished but otherwise unadorned wood, such as this pier table at New York’s Merchant’s House Museum, were replacing pieces with stenciled decoration and carved, gessoed, and gilded components (e.g., the column capitals, cornucopias, and eagles on Jumel’s furniture). Some items in the mode of the 1820s were still made, but their proportions were increasingly heavy. If Jumel had purchased furniture in 1833, what she acquired would have looked different than the surviving pieces identified with her.

|

Overall, the items she chose were handsomely

finished, up-to-the-minute in style, and eminently suitable for an upper-middle-class

household. They were not top of the line, however. This is unsurprising. In 1827 Jumel's resources were limited. Equally importantly, she liked a bargain. She and her husband are known to have acquired used furniture on occasion and bought items at auction. As a relative said of a bed at the mansion, he believed "the interest Madame had in it was because she purchased it cheaply" (New York Herald, January 31, 1873, p.11).

In 1827 Jumel would have had a variety of options for buying a large quantity of furnishings at a discounted price. Advertisements appeared in the New York's newspapers on a weekly basis for auctions of used furniture (from estates or families moving house). Bargains were available on new furniture too. The cabinetmaking market was competitive in New York, especially after the Panic of 1825 depressed sales. Some furniture was even made specifically for auction, drawing complaints from craftsmen who found themselves undersold (John L. Scherer, New York furniture at the New York State Museum, 1983, p. 56, fig. 52a). Robert Fisher's frequent moves—he had seven addresses on the Lower East Side over the course of fourteen years in New York—hint at a possible struggle for financial stability. Did Jumel give him her business because he was flexible on price or willing to offer a discounted rate for a bulk purchase? We don't know. But she acquired a diverse range of items, suggesting that she chose from whatever he happened to have in stock. Alternately, she may have picked up the furniture on the secondary market, at one of various auctions featuring the stock in trade of cabinetmakers (typically unnamed) suffering from "declining business" (e.g., Commercial Advertiser, March 26, 1827, p. 3).

Whatever the source, she could not have anticipated the long-term results of her purchase. In 2011, I gave a talk at the Mid-Manhattan Library titled "The Morris-Jumel Mansion: A Time Capsule of Old New York." The term "time capsule" was more accurate than I realized. Thanks to Jumel's care for her possessions and the efforts of loyal guardians—among them her great-niece and then the Daughters of the American Revolution (who managed the Morris-Jumel Mansion for decades)—the house, with its historic collection of furniture, allows us to reassess the production of a forgotten New York cabinetmaker.

In 1827 Jumel would have had a variety of options for buying a large quantity of furnishings at a discounted price. Advertisements appeared in the New York's newspapers on a weekly basis for auctions of used furniture (from estates or families moving house). Bargains were available on new furniture too. The cabinetmaking market was competitive in New York, especially after the Panic of 1825 depressed sales. Some furniture was even made specifically for auction, drawing complaints from craftsmen who found themselves undersold (John L. Scherer, New York furniture at the New York State Museum, 1983, p. 56, fig. 52a). Robert Fisher's frequent moves—he had seven addresses on the Lower East Side over the course of fourteen years in New York—hint at a possible struggle for financial stability. Did Jumel give him her business because he was flexible on price or willing to offer a discounted rate for a bulk purchase? We don't know. But she acquired a diverse range of items, suggesting that she chose from whatever he happened to have in stock. Alternately, she may have picked up the furniture on the secondary market, at one of various auctions featuring the stock in trade of cabinetmakers (typically unnamed) suffering from "declining business" (e.g., Commercial Advertiser, March 26, 1827, p. 3).

Whatever the source, she could not have anticipated the long-term results of her purchase. In 2011, I gave a talk at the Mid-Manhattan Library titled "The Morris-Jumel Mansion: A Time Capsule of Old New York." The term "time capsule" was more accurate than I realized. Thanks to Jumel's care for her possessions and the efforts of loyal guardians—among them her great-niece and then the Daughters of the American Revolution (who managed the Morris-Jumel Mansion for decades)—the house, with its historic collection of furniture, allows us to reassess the production of a forgotten New York cabinetmaker.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, May 2, 2016

Appendix: Some further comments on Robert Fisher

|

Art historians know that attributions research is a tricky game. Styles that become popular are copied over and over, making it difficult to determine their originator. It is equally difficult to tell where an innovator's production stops and that of copyists begins. The problem is compounded by the fact that cabinetmaking firms had had not only regular employees but also craftsmen who worked on a piecework or temporary basis. Matthew A. Thurlow has pointed out the difference between the carving on the arm supports of two chairs made for the U.S. Senate in the workshop of Thomas Constantine (1818–19)—evidence that more than one hand was involved in filling the commission ("Aesthetics, politics, and power in early-nineteenth-century: Thomas Constantine & Co.'s furniture for the United States Capitol, 1818–1819," in American Furniture 2006, ed. Luke Beckerite (Milwaukee: The Chipstone Foundation, 2006), p. 202, fig. 22). The Robert Fisher pier tables with cornucopias reveal the hands of multiple carvers too, while still being sufficiently alike to argue for their origin within a single workshop. To them we could add two additional works that are convincingly in Fisher's manner, although without cornucopias or eagles: a stenciled, veneered, and ebonized wardrobe at the Museum of the City of New York and an ebonized table serendipitously on long-term loan to the Morris-Jumel Mansion from the Metropolitan Museum that has fruit-and-foliage stenciling extremely close to that on other pieces by Fisher and and was given to the museum by the same donor as pier table B and the secretary-bookcase.

|

|

A pair of pier tables formerly with Connecticut dealer Charles Clark present more of a puzzle. They are said to have come from the Jumel Mansion and to have been in the catalogue of the sale held at Silo's in 1916. This provenance is probably accurate. A photograph of the front parlor of the mansion circa 1887 shows what appears to be one of the two, standing against the wall beneath a mirror. It and its pair may be the matched set of console tables (an alternate name for pier tables) that sold at the Silo sale for the handsome price of $270 the pair (lots 208 and 209). Furniture that was fully veneered like these tables, rather than ebonized, tended to bring the highest prices. Whether they are works by Robert Fisher remains uncertain. They have the characteristic large paws, but are decorated beneath the plinth with a form composed chiefly of leaves. Was this leaf form, like the eagles, an alternative decoration from Fisher's workshop or the product of another atelier? I incline to the former possibility, especially given the Jumel provenance, but the matter remains unresolved. Photographs of the sides of the paw feet and sharper images of the column capitals might provide further clarification.

A sofa at Winterthur, considered to be New York-made, is even more perplexing. It shows certain similarities to the Fisher sofa at the Morris-Jumel Mansion—most notably the double-stripe stenciling on the scrolled armrests and the acanthus leaves stenciled in bronze powder on the seat rail. The fruit-and-foliage stenciling on the center of the seat rail also nods at works by Fisher. The carving on the feet, however, is unique and of particularly high quality. Could this creation of great elegance represent Fisher working for a deep-pocketed and demanding client? Or was it made by a Baltimore master, in a style that Fisher drew on after moving to New York? For now, these questions have no answer. |

|

A sofa at the Baltimore Museum of Art is of particular interest in demarcating the dimensions of Fisher's production. It was first remarked at an auction in Baltimore County in the mid-1970s and could be from Baltimore region, based on the woods used in its construction. Significantly, the front brackets (the areas just above the paws) are ornamented with an eagle holding two swags of drapery. Had Fisher made or seen work like this in Baltimore that inspired his New York eagles? Again, a definitive answer remains elusive.

|

In contrast, other riffs on themes that Fisher employed are clearly not from his hands. Erik Rini has demonstrated that the firm of Edward Holmes and Simeon Haines (1825–1830) produced pier tables with fruit-and-foliage stencils, such as this labeled example from the Geneva Historical Society. Several features of these tables are distinguishable from those of Fisher: the shape of the column capitals, the feet (paw feet, when used, are elevated at the back as if on high heels), and the bulging table aprons (the shape is called a "bolection molding"), a form seen on Fisher's bookcases but not his pier tables. If cornucopias appear on a Holmes and Haines table, they fit closely beneath the plinth and have a rectilinear quality. Indeed, the characteristics of Holmes and Haines tables are sufficiently distinctive that it is possible to pick out other works from their shop. To the Geneva example, I suggest we add similar tables in the Brooklyn Museum (42.182) and the Dallas Museum of Art (1985.B.49), both without attribution at the time of this writing in their institutions’ respective online catalogues.

|

It could be argued that Holmes and Haines rather than Fisher introduced the fruit-and-foliage stenciled motifs in New York. But they established their partnership in 1825, at least a year after Fisher set up shop in the city, and neither is known to have come from Baltimore, the most likely source for the idea of combining fruit-and-foliage and classically-inspired stenciled patterns. Additionally, Fisher seems to have produced a more varied body of work then that so far associated with Holmes and Haines, making him a more likely trendsetter. Nevertheless, a definitive conclusion on which workshop used such stenciling first awaits the unearthing of further evidence.

|

What is clear is that the style enjoyed rapid diffusion. For example, this convertible settee by Chester Johnson, a fancy chair maker who moved from Albany to New York City but continued to serve the upstate market, features Fisher-like stenciled and gilded baskets of fruit and bronze-powder stenciling of fruit and foliage. It is thought to have been made around 1827, the first year Johnson appeared in the New York City directory.

|

The New York City firm of Williams & Dawson experimented with similar motifs in the second half of the 1820s, as did Roswell A. Hubbard (active in New York between 1834 and 1836) in the following decade. After the middle of the 1830s, however, the style

appears to have been abandoned.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, May 2, 2016