Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion–Part 2:

The Mansion as Eliza Jumel Knew It?

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 1, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, and part 8.

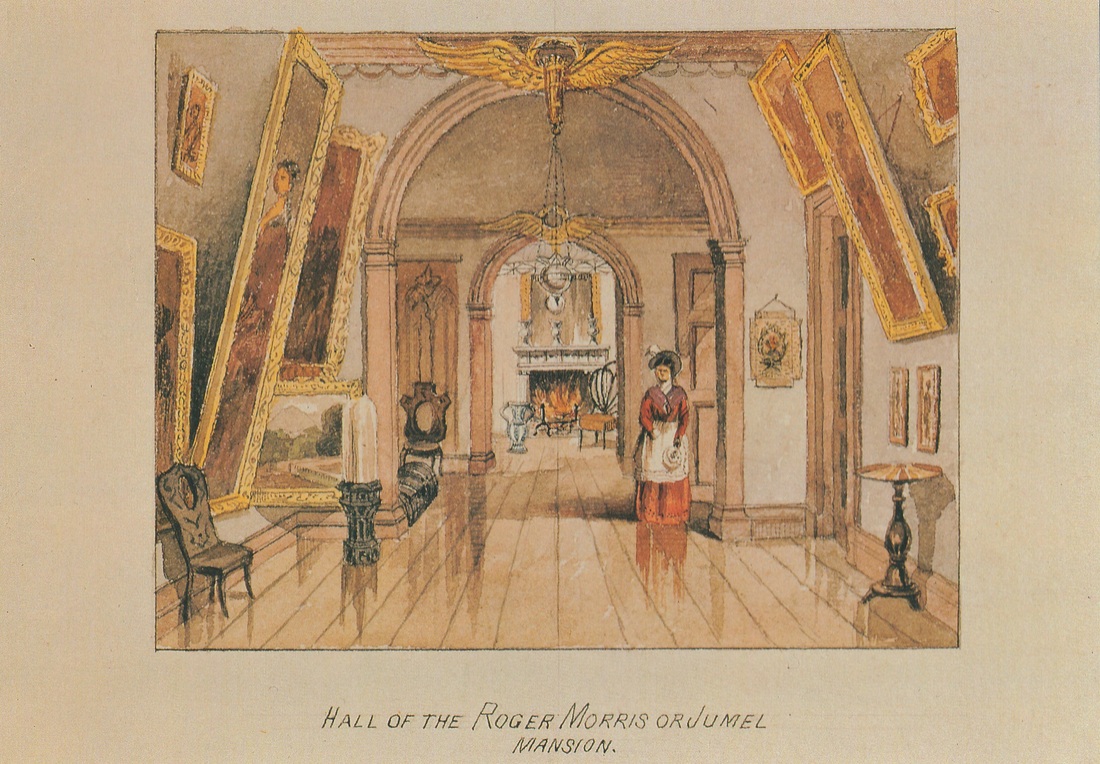

Among the postcards in the gift shop of the Morris-Jumel Mansion, my favorite is one that reproduces a watercolor of the hallway in the nineteenth century. The waxed floors shine, paintings line the walls, and in the background, the octagon room is ready to welcome guests. But I have been bothered by two unsolved questions: 1) when was this image painted and 2) how accurate is it? Are we looking at an idealized picture of what the mansion might have been like in Eliza Jumel's day or an exact representation of the hallway during her lifetime?

|

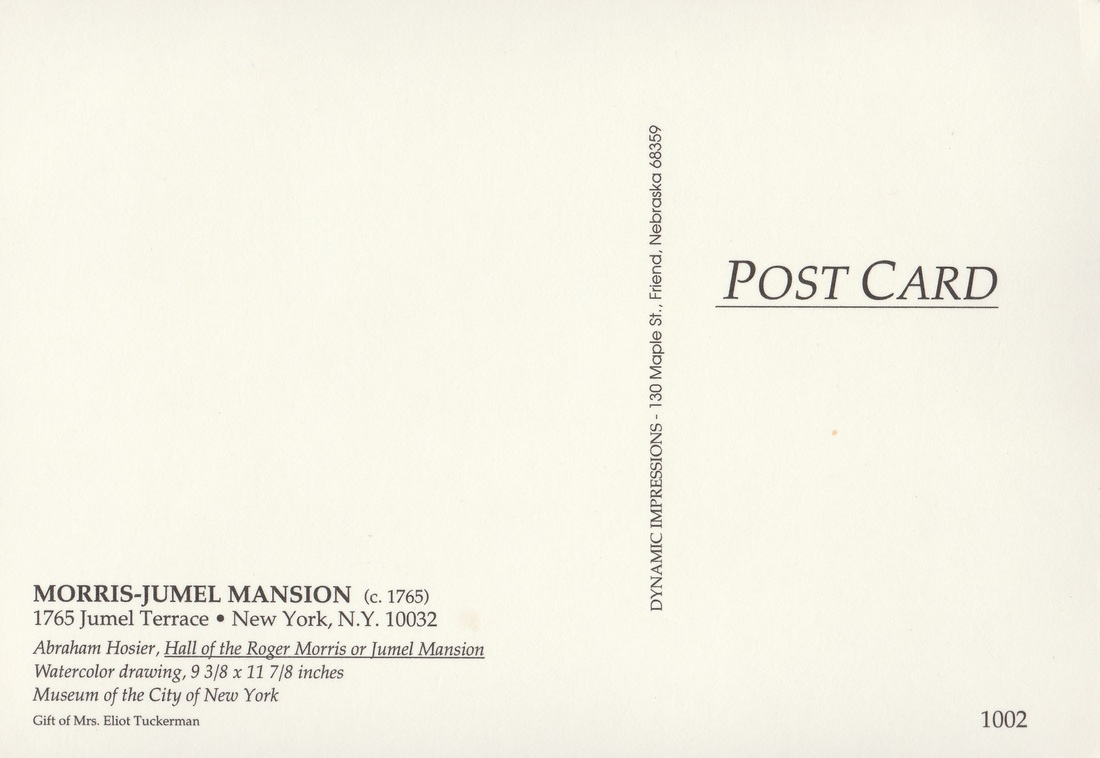

Recently I made progress on answering both these questions. I discovered a wood engraving that reproduces the watercolor (or, less likely, served as the model for it) in the December 1, 1875, issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine. It was used to illustrate an article on historic sites near the Hudson River by Benson J. Lossing, who had also written about the Jumel Mansion in 1873 (without the view of the hallway) for Appleton's Journal of Literature, Science, and Art. Therefore the engraving—seen here in a fine impression owned by the New York Public Library—was created no more than ten years after Eliza Jumel's death in 1865.

|

Not long after discovering this image, I took another look at the magnum opus of William H. Shelton, first curator of the Morris-Jumel Mansion. In his book, The Jumel Mansion (1916), Shelton reproduced several nineteenth-century photographs of the interior of the house. This 1887 image of the hall is enlightening.

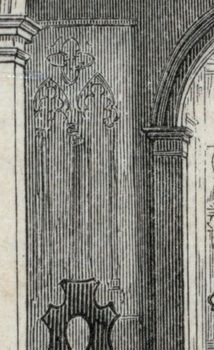

At first glance the space, cluttered with bric-a-brac, seems to have little relationship to the sleek interior depicted in the engraving and watercolor. A closer look, however, reveals similarities. The carved and gilded wings surmounting the arches feature in all three images (and hang in the mansion today). The swaglike floral motifs forming the upper border of the wallpaper are clearly the source for the swags that appear in the same location in the watercolor and engraving. The chair at the right side of the archway at the end of the hall appears in the engraving and watercolor too, although on the left rather than the right side of the arch.

|

Several paintings appear in the same locations in all three images, most notably the large portrait of Eliza with her great-niece and great-nephew that hangs in the upstairs hallway of the mansion today. Adjacent to it, we can see a landscape and a picture of a man or youth wearing a broad-brimmed hat. The latter may be a Beggar Boy remarked by Lossing in his 1873 article for Appleton's as hanging near the family portrait and listed in an inventory made shortly after Eliza's death as Beggar Boy and Dog.

|

|

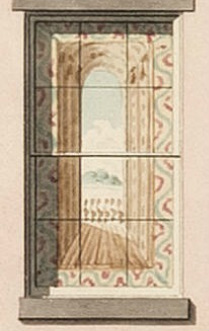

In both the engraving and the watercolor, the window at the end of the hallway is covered with a blind decorated to imitate a Gothic window. Shades such as this, painted with transparencies of landscapes or architectural elements, were available commercially in the nineteenth century and crafted at home by women as well.

|

The small hanging suspended from a nail to the right of the first archway is probably a keepsake described by Lossing in his 1875 article in Harper's as "an elaborate embroidery of flowers, surrounded by a golden chain on a white ground," supposedly made by Empress Josephine of France. In 1873 and 1875, Lossing mentioned two items of furniture in the corridor as well: a small, circular, inlaid table with a cameo profile of Voltaire in the center and, on the floor, "a cylindrical leather trunk," said (surely inaccurately) to have been used by Napoleon during his Russian campaign. Both pieces may be seen in the watercolor and engraving.

By the time the photograph of the hallway was taken in 1887, the trunk and the embroidery were gone from the hall. The painted blind had disappeared, too—a victim of age or changing taste—and the entryway had become more cluttered. A yarn winder, flax wheel, and spinning wheel competed with the paintings on the left side of the corridor and, opposite, two unmatched chairs had joined what may be the “Voltaire” table.

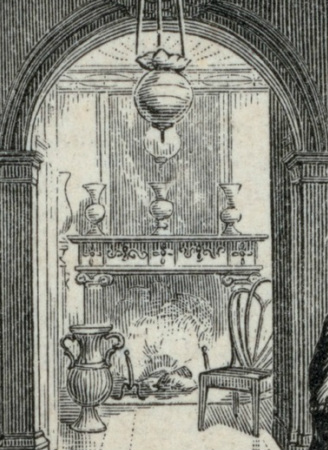

Another photograph published by Shelton records the appearance of the octagon room (seen beyond the archway at the end of the hall in the engraving and watercolor).

Another photograph published by Shelton records the appearance of the octagon room (seen beyond the archway at the end of the hall in the engraving and watercolor).

Comparing the photograph with the engraving, we find the fireplace and the mirror above it in both. The mantel survived into the Morris-Jumel Mansion's first years as a museum, as can be seen in an early twentieth century image (although if its carved or applied decoration was not an invention of the artist, it had been stripped off by the time the latter photograph was taken).

|

Other elements of the décor are more perplexing. Front and center in the photograph is a curious, freestanding object—possibly a torchiere (floor lamp). It may be the item partially visible to the left of the fireplace in the engraving. The unlikely chair next to the hearth could be an interpretation (with some artistic license) of a shield-back, Hepplewhite-style chair that was in the dining room of the mansion in 1887.

|

The

carpeting seen in the photograph does not appear in the engraving or

watercolor, whether because it had not been installed yet—a man who visited the

house around 1880 said that all the floors, including that of the octagon room,

were of bare, highly polished wood, although he was writing from memory some

twenty-five years later—or because the artist prioritized the unity given by

the floorboards to the enfilade of rooms.

One element of the mansion’s interior is left to our imagination. Lossing, in his 1875 article, wrote that "the walls and wood-work of the hall are delicate blue, white, and gold, and the general effect is very striking when seen for the first time." Looking closely at the 1887 photograph of the hallway, it appears that blue or gold may have been used to pick out moldings that decorate the arches and the bases and capitals of the pilasters. Additionally, the ceiling of the hallway appears slightly darker in color than the molding at the top of the wall: might it have been painted (or papered in) gold? Perhaps that is an illusion of the lighting.

_

One element of the mansion’s interior is left to our imagination. Lossing, in his 1875 article, wrote that "the walls and wood-work of the hall are delicate blue, white, and gold, and the general effect is very striking when seen for the first time." Looking closely at the 1887 photograph of the hallway, it appears that blue or gold may have been used to pick out moldings that decorate the arches and the bases and capitals of the pilasters. Additionally, the ceiling of the hallway appears slightly darker in color than the molding at the top of the wall: might it have been painted (or papered in) gold? Perhaps that is an illusion of the lighting.

_

Did the rooms look more or less like this at the time of Eliza Jumel's death in 1865? Absent new visual or documentary evidence, we can't be certain. Possibly the wallpaper and/or the painted detailing of the woodwork were updated. But money was tight in the decade or so following Jumel’s decease because of expensive battles over her estate. It is unlikely that her relatives, who were living in the house during the litigation, undertook any major redecoration campaigns. Certainly the house was already richly furnished in Jumel’s later years. According to a visitor in 1855, "Costly paintings (and among them a genuine Rubens), articles of vertu, presents from noble and distinguished persons, autographs, and everything that is rare and costly and curious, may be seen there in lavish profusion." Probably the engraving published in 1875 and its associated watercolor offer a reasonable approximation of the entryway as Jumel knew it in her final days. They provide an insight, if only an imperfect one, into her personal taste.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, March 8, 2016

Note on the Sources: Benson J. Lossing’s 1873 account

of the Jumel Mansion was published in Appleton's

Journal of Literature, Science, and Art, August 2, 1873. The guest who

mentioned seeing the highly polished floors "about 1880" was Charles

Burr Todd (In Olde New York: Sketches of Old Times and Places in Both the State and the City, 1907, pp. 77n1 and 83).

The 1855 visitor is unnamed, but his or her account appeared in an 1855 article

in the Albany Express that was

reprinted in the Pioneer and Democrat

(Washington Territory), November 14, 1856, under the title "A personal sketch

of Madame Jumel, wife of Aaron Burr." K. Hadjiafxendi and P. Zakreski discuss

the use of blinds painted with transparencies in Crafting the Woman Professional in the Long Nineteenth Century:

Artistry and Industry in Britain, 2013, pp. 58–64. The watercolor reproduced on the Morris-Jumel Mansion's postcard is in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York and may be seen on the museum’s website (clickable image at the top left). The digital image of the wood engraving that I have used in this article came from the New York Public Library’s digital collections database. Their copy of the engraving makes part of a group of historic images of New York City assembled by a local doctor, Thomas Addis Emmet, and bound together in 1880 in a multivolume set that the library owns today.

An Update

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

|

In "A Peek into the Past: The Morris-Jumel Mansion as Eliza Jumel Knew It?" I speculated that a chair with an unusual back, depicted in the octagon room of the Jumel Mansion in the nineteenth century, might be identifiable with a Hepplewhite chair visible in the house's dining room in 1887. I was wrong.

|

|

I discovered my error on a visit to the mansion yesterday. The recently rearranged Eliza Jumel bedroom features a Hepplewhite chair previously in storage. Although similar to the chair seen in the 1887 photograph of the dining room, its back terminates at the top with three arches rather than a shield shape. The chair in the bedroom, which is said to have belonged to Jumel—and not the one in the archival photograph of the dining room—appears to be the item illustrated in the nineteenth-century watercolor of the mansion interior. Possibly it belonged to the same set as the dining room chair (I reserve my opinion until I have seen the front of the chair in the bedchamber, which I photographed from the doorway to the room). The Morris-Jumel Mansion always has surprises for visitors!

|

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, May 12, 2016