Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion—Part 6:

Envisioning an Eighteenth-Century Dining Room

By Margaret A. Oppenheimer, author of The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel

Looking for a different secret of the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Click these links for part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 7, and part 8.

How was the dining room of the Morris-Jumel Mansion decorated during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries? The earliest surviving images, dating from the 1880s, show it cluttered with knickknacks and hung with four different wallpapers that reach up to and even cover the ceiling. But an intriguing bit of evidence offers a tantalizing hint at what came before. The factoid is found in the Historical sketch of Washington's headquarters by Emma A. F. Smith, a handbook produced after the Morris-Jumel Mansion was turned into a museum at the beginning of the twentieth century.

|

Eliza Jumel's great-niece and namesake, Eliza Jumel Chase Caryl, provided Smith with a small detail about the decoration of the mansion in her great aunt's day. The dining room walls, she said, "were a dark green, about the color of a lily leaf, and furnished at the top with a band of gold, three fingers wide."

|

Most unfortunately, Caryl did not specify the era at which the green paper hung in the dining room, nor whether it was chosen by Eliza and Stephen Jumel, who purchased the house in 1810, or if instead they found it on the walls when they acquired the property.

|

When, then, could the paper have been manufactured? Certainly solid-colored wallpapers had come into fashion by the time the Morris-Jumel Mansion was built in the mid-1760s. Blue, green, and straw were the favored hues, with narrow papier-mâché borders, covered with gold leaf, fastened to the top of such wall coverings to form a gilded border. Benjamin Franklin adopted this mode for one of the rooms in his home in 1765, instructing his wife to "paint the wainscot a dead white, paper the walls blue, and tack a gilt border around the cornice." Similar wall coverings were installed in the Ballroom (blue paper) and Supper Room (green paper) of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg in the late 1760s.

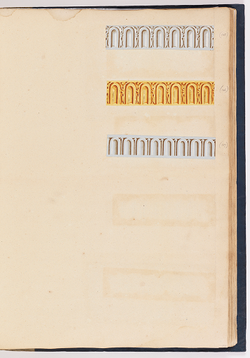

The style was still in vogue two decades later—George Washington inquired in 1784 about acquiring a blue or green paper and papier-mâché borders—but by then a range of decorative paper borders were available as well, soon displacing papier-mâché. A sample book from a French wallpaper manufacturer, dating from approximately 1785 to 1795, contains several narrow borders designed to imitate gilded cornices. Similar examples from another French factory were made in 1799.

More elaborate borders were available too. In 1787, for instance, Gerardus Duyckinck of New York City offered his customers monochrome green and blue, American-made papers, accompanied by "Festoon Borders." The overall effect is captured in this watercolor, which must date from the second half of the 1790s, judging from the women's clothing. As you can see here, from the mid-1780s through the 1820s, paper borders were pasted not only just below the ceiling (where they were called "friezes") but also around architectural elements such as doors, fireplaces, and wainscoting (the wood paneling covering the lower portion of walls).

Wide friezes were preferred to narrow ones by the beginning of the nineteenth century, so if Eliza Caryl was accurate in describing the Morris-Jumel dining room border as "three fingers wide"—approximately 2 inches (five centimeters) or a shade over, measured on a woman's hand—then the most likely time for its production would have been ca. 1765–ca. 1785 (if the border was papier-mâché) or ca. 1785–ca. 1800 (if a printed border). (Although Thomas Chippendale mentions installing printed borders in England in the 1760s, early references to gilded borders in America refer to the paper-mâché type, suggesting that the printed versions did not arrive on our shores until after the Revolutionary War.) In either case, the wallpaper would have been something that Eliza and Steven Jumel found on the walls of the dining room when they acquired the mansion and perhaps left in situ for some years.

Using PowerPoint and Photoshop, I have developed some rudimentary mockups suggesting how the dining room might have looked. My first two images show a narrow gilt border at the top of the wall, crowning sidewalls of two different shades of green.

Using PowerPoint and Photoshop, I have developed some rudimentary mockups suggesting how the dining room might have looked. My first two images show a narrow gilt border at the top of the wall, crowning sidewalls of two different shades of green.

|

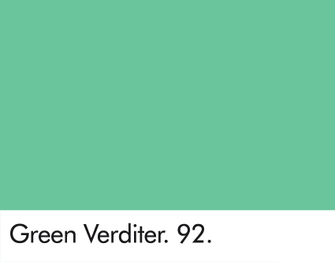

The colors of the sidewalls were inspired by a fragment of wallpaper hung about 1762 in the James Geddy House in Williamsburg, Virginia. The brighter green area of the fragment was hidden from the light by an overlapping sheet of wallpaper and retains its original coloring. The darker green portion reveals how the pigment was altered by years of light exposure. My paired images, provided with similarly colored papers, suggest how the Morris-Jumel Mansion wallpaper might have looked 1) as originally hung and 2) some years later.

|

|

It is possible that gold borders were used to outline the architectural features and not just the top of the wall, so I created a third mockup modeling that possibility. (In describing the decoration of the dining room, Eliza Caryl was probably relaying information shared with her by her great aunt, and what she was told or remembered might have been incomplete.)

|

I suspect that my borders in these mockups appear wider and more prominent than they should—I did not have the precise measurements of the wall with which to determine the proportions. Also, the brighter of my two green papers is not an exact match for the light-protected area of the Williamsburg sample, which is a slightly bluer green, and my darker paper differs modestly from its model as well. However, I hope that the three reconstructions will give you a rough impression of what the dining room might have looked like in 1810, when Eliza and Stephen Jumel acquired the home called Mount Morris, the house we know today as New York's Morris-Jumel Mansion.

|

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, September 1, 2016

Note on the Sources: Jonathan Thornton discusses eighteenth-century papier-mâché borders in "The history, technology, and conservation of architectural papier-mâché," Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 32, no. 2, article 7 (1993): 165–76. The modern restoration of the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg is described in Roberta Laynor, "Governor's Palace 2006 Closing Summary," Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - RR1709, July 2006 (Williamsburg, Virginia, 2007); available at http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR1709.xml. George Washington's inquiry about wallpaper with papier-mâché borders has been published online by the National Archives and is available at http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0037. Benjamin Franklin's instructions to his wife about decorating a room are quoted in Alan Victor Sugden and John Ludlum Edmundson, A history of English wallpaper, 1509–1914 (London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., [1925], p. 51. Chippendale's use of paper as well as papier-mâché borders is referenced in the same publication, e.g., pp. 83–85. The wallpaper ad placed by Gerardus Duyckinck appeared in the Daily Advertiser on April 12, 1787, and was published by William Kelby in "Notes on American Artists," New York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 4, no. 1 (April 1920): 27. For the wallpaper fragment from the James Geddy House, see Frank S. Welsh, "Investigation, Analysis, and Authentication of Historic Wallpaper Fragments," Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 43, no. 1 (Spring 2004), 91-110. Note that on page 92, the fragment is said to have been installed in the house in the "1960s," but this is clearly a typographical error for "1760s," as the discussion on pages 92–93 makes clear. Those who have read part 5 of my Secrets of the Morris-Jumel Mansion, about an eighteenth-century wallpaper fragment from the Morris-Jumel, will note the similarity between its bulbous leaf forms and those of the smallest leaves on the Colonial Williamsburg fragment—another indicator that the Morris-Jumel remnant could date from the 1760s.

An Update

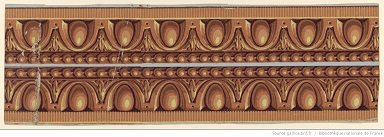

Since writing the study above, I came across two more images showing solid-colored wallpaper with gold borders. I include them here to offer a fuller picture of the possibilities available to the eighteenth-century homeowner. Most probably the first portrait was painted in England and the second in Germany. Wall treatments fashionable in Europe, such as those seen in these pictures, were adopted quickly in the United States.

Copyright Margaret A. Oppenheimer, October 18, 2016